The Angel of the Annunciation

1482 On panel Städelisches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am MainThe angel alights on a city street, wings raised and cloak billowing with air from the sudden landing. Gabriel delivers God’s message: the Virgin will bear his son. She kneels in acceptance, hands crossed in prayer, her bedroom illuminated by the Holy Spirit. These two paintings formed the pinnacles of a thirteen-foot tall altarpiece. To compensate for their precipitous location, Crivelli designed this Annunciation in steep perspective, correcting for the view from below.

Photo © U. Edelmann - Städel Museum - ARTOTHEK.

The Annunciate Virgin

1482 On panel Städelisches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am MainThe angel alights on a city street, wings raised and cloak billowing with air from the sudden landing. Gabriel delivers God’s message: the Virgin will bear his son. She kneels in acceptance, hands crossed in prayer, her bedroom illuminated by the Holy Spirit. These two paintings formed the pinnacles of a thirteen-foot tall altarpiece. To compensate for their precipitous location, Crivelli designed this Annunciation in steep perspective, correcting for the view from below.

Photo © U. Edelmann - Städel Museum - ARTOTHEK.

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius

1486 On canvas, transferred from panel The National Gallery, London, Presented by Lord TauntonInscribed: OPUS CAROLI CRIVELLI VENETI 1486; bottom: LIBERTAS ECCLESIASTICA (Liberty under the Church)

Monumental in scale, this altarpiece commemorates a special occasion. In 1482 the Pope granted the right of self-governance to Ascoli Piceno, the biggest city in the Marches. Its citizens celebrated their liberty annually, on the feast day of the Annunciation (25 March). Here their patron Saint Emidius interrupts the angel Gabriel to present a model of the newly liberated city and invite divine protection.

Conceptually ambitious and technically accomplished, this painting showcases Crivelli’s mastery of artifice. A plunging perspective dramatizes the story and highlights the Virgin’s house, depicted here as an outrageously deluxe palace. Crivelli compressed her Annunciation and Conception into a single moment. She awaits God’s message as the Holy Spirit penetrates her bedchamber, its diagonal descent traced in a beam of light. Crivelli applied it in gold, defying the composition’s perspectival recession and investing this shimmering ray with symbolic value.

Photo: © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY.

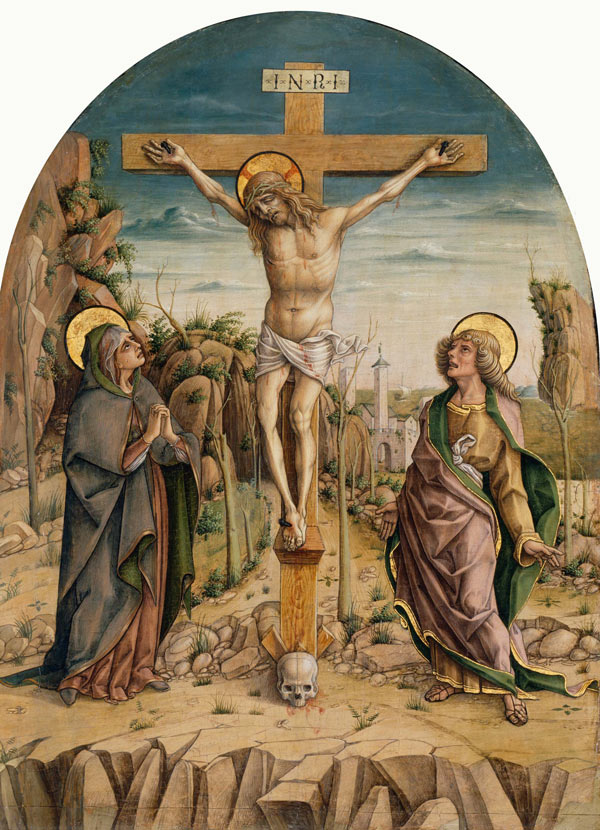

The Crucifixion

c. 1487 On panel The Art Institute of Chicago, Wirt D. Walker FundChrist’s battered body hangs from the cross, blood streaming down his arms. Crivelli located the scene in the familiar landscape of the Marches with its steep mountains and bustling sea ports. He even transforms Jerusalem into a coastal port. Below, the jagged outcrop functions like a parapet, ensuring a respectful distance between Christ and devotee.

The Dead Christ between the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist

c. 1475 On canvas, transferred from panel, with overpainting by by Luigi Cavenaghi (1844–1918) Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, Gift of Arthur SachsWhen Christ died, the earth split and rocks shook. A broken parapet acknowledges the transformational event. Behind it, the Virgin Mary weeps over her dead son. John the Evangelist takes one arm and Christ’s hand rests on his sleeve, the bloody stigmata opening through lifeless flesh. At some point in the past, this painting lost its center, perhaps due to fire damage. In the early twentieth century, a restorer reconstructed Christ’s body, on the basis of extant Crivelli paintings of the same subject.

Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

The Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels

c. 1472 On panel Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson CollectionDrained of life, Christ’s rigid body exposes his past suffering. Torn flesh encompasses the gaping stigmata and savage thorns penetrate his gaunt brow. Mouth open, head thrown back in anguish, Christ’s expression acknowledges this harrowing moment. Crivelli evoked the dead body’s stony color and rigor mortis with lapidary precision, echoed in the faceted tunics of both mourning angels. This pinnacle of an altarpiece was repurposed for a collector with the modern addition of brocade tooled in gold.

The Dead Christ with the Virgin, Saints John and Mary Magdalene

1485 On panel Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Anonymous Gift and Julia Bradford Huntington James FundInscribed: OPUS CAROLI CRIVELLI VENETI 1485

Crivelli abridged Christ’s descent from the cross and entombment into a single, grief-stricken moment. The Virgin, Mary Magdalene, and John the Evangelist mourn together, framing the Savior’s corpse beneath a garland of ripe fruit. It may allude to the sacrament of the Eucharist (Christ made present at the Mass through bread and wine), which was described in contemporary sermons as the food that exceeded all others in sweetness. Crivelli took great pride in this painting, signing it in gold on the left side of the parapet.

Photograph © 2015 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Lamentation

1470 On panel Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society purchase, General Membership FundPorto San Giorgio Altarpiece

Wailing in anguish, the Virgin entombs her son. Mary Magdalene and John the Evangelist assist. Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus kneel in prayer before Christ, his body bearing the wounds from the Crucifixion. His crown of thorns projects from the painted surface in high relief. Crivelli transformed this traditional symbol of Christ’s agony into virtuoso ornament, transcending the boundaries of painted illusion and investing it with presence. He deployed a similar technique for Saint Catherine’s crown.

Photo: Bridgeman Images.

The Last Supper

1482 On panel Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Catherine J. Tudor-Hart EstateChrist’s final meal pulses with life. The Apostles engage in animated debate, attend to his final words and feast on the food before them. At either side, they offer each other cucumbers. This vegetable is not found in biblical accounts but instead alludes to the painter Crivelli with an unusual signature device. His tiny composition is masterfully designed. The painter carved out a plausible space for all thirteen figures, revealing his practical facility with the principles of perspective. This fragment of the San Domenico altarpiece occupied its lowest register, where Crivelli’s Last Supper could be appreciated for its lively interactions and intriguing detail.

Photo: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Christine Guest.

The Nativity (Adoration of the Shepherds)

c. 1491 On panel Musée des Beaux-Arts, StrasbourgCrivelli’s setting confers on this Nativity a humble majesty. Driven into the earth, three posts stake out the site of Christ’s birth. The biblical hut they support is no simple shed. With finely carpentered planks and a carefully planned interior, it shares all the architectural sophistication of distant Bethlehem. In the faraway fields, shepherds witness the heavenly sign of his birth and arrive in adoration. The vast landscape in between suggests the distance of their journey and relocates this revelation from the arid Holy Land to a verdant present.

Photo: Musées de Strasbourg.

Saint Anthony of Padua

c. 1485–90 On panel Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.Second only to the founder in the Franciscan pantheon of saints, Anthony died in Padua in 1231. Here he wears the order’s brown habit and knotted cord. This barefoot friar gazes towards the heavens, mouth open, both hands joined in prayer. He is as much a model of piety as the object of devotion. Crivelli honored this saint with a purple silk textile. In the distance, a stone portal and medieval towers recall the Marches’ many fortified cities.

Saint George

1472 On panel Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers FundSan Domenico, Fermo Altarpiece

Unlike the Gardner’s Saint George, this legendary dragon slayer cuts a debonair figure. Deed done, he poses over his prey, resplendent in a fantasy of ancient Roman armor. The lion on his belt remains dubious of George’s battlefield prowess and looks askance at the youthful victor’s sword hand, resting casually on one hip. In a tour de force of material imitation, Crivelli depicted the metallic armor plates in paint. He reserved gold for the background alone, part of which is a modern addition.

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Saint George Slaying the Dragon

1470 Tempera, gold and silver on panel Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, BostonPorto San Giorgio Altarpiece

Crivelli compressed the story of Saint George – who saved a city and its princess from the marauding dragon – into a single, dynamic moment. Run through with a lance, the monster roars in agony, frightening this saint’s steed. The horse rears up and shies away, eyes wide with fear. In a feat of remarkable horsemanship, George stands, drops the reins and draws his sword to deliver the death blow. A rare subject for the side panel of an altarpiece, this image constituted the right side of the Porto San Giorgio polyptych.

Learn more about the Gardner's conservation of this work in Beneath the Surface.

Saint James Major

1472 On panel Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Helen Babbot SandersSan Domenico, Fermo Altarpiece

James joined Christ in prayer before his arrest. Crivelli depicts the barefoot Apostle with Christ-like hair, beard and facial features, acknowledging his close relationship with the Savior. In the Middle Ages, James became the patron saint of pilgrimage and Crivelli duly furnished him with the pilgrim’s cockle shell, hat and staff. Along with Saint George and Saint Nicholas of Bari, this painting once constituted a part of the San Domenico, Fermo altarpiece’s main tier. Crivelli united them with a low parapet, a section of which is visible behind James.

Saint Nicholas of Bari

1472 On panel Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of the Hanna FundSan Domenico, Fermo Altarpiece

Born in the third century AD, Nicholas was ordained a priest and rose to the rank of bishop. Crivelli outfitted this saint in the ceremonial attire of his office. Nicholas peers suspiciously from a richly embroidered cope as if encased in liturgical armor. In one hand, he grasps a pastoral staff, or crozier, while balancing three golden orbs in the other. These traditional symbols commemorate his generosity to three impoverished women.

Photo: © The Cleveland Museum of Art

Saint Peter

c. 1470 Brown ink, brown wash, and white gouache on paper, laid down Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Charles A. LoeserThis is Crivelli’s only surviving work on paper, rare testament to his lightning line. Confident pen strokes charge down Peter’s back. These marks define the cloak’s edge, lending its fabric an electric vitality. He excavated forms with energetic hatching, densely modeling each fold in light and shade. Even in this small drawing, Crivelli delivers the same graphic precision that underpins his largest paintings.

Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Saint Peter

c. 1470 On panel Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of E.M. SperlingBoth paintings of Saint Peter are fragments, parts of two separate altarpieces. Each composition relies on meticulous draftsmanship. Crivelli’s nearby drawing may have been preparatory for the Detroit painting. Their general compositions align closely, but details differ. In the Detroit picture, Peter wears a simplified cloak and sports a full head of hair. The painting is also larger, so this drawing cannot be the final study. Crivelli may have kept this sheet in his workshop, relying on it as a model for other versions of the same saint, like the New Haven painting.

Photo: Bridgeman Images.

Saint Peter

c. 1470 On panel Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Gift of Hannah D. and Louis M. RabinowitzBoth paintings of Saint Peter are fragments, parts of two separate altarpieces. Each composition relies on meticulous draftsmanship. Crivelli’s nearby drawing may have been preparatory for the Detroit painting. Their general compositions align closely, but details differ. In the Detroit picture, Peter wears a simplified cloak and sports a full head of hair. The painting is also larger, so this drawing cannot be the final study. Crivelli may have kept this sheet in his workshop, relying on it as a model for other versions of the same saint, like the New Haven painting.

Saints Anthony Abbot and Lucy

Not in exhibition 1470 On panel Krakow National Museum, Krakow, Collections of the Princes Czartoryski FoundationPorto San Giorgio Altarpiece

The founder of Christian monasticism, Anthony Abbot sought divine truth in the deserts of northern Egypt. In contrast with Lucy’s crystalline complexion, his sunbaked skin and long beard attest to the ascetic life of this early Christian hermit. Anthony wears the black habit, or uniform, of a Hospitaller brother. These laymen established hospitals in this saint’s name across Europe for victims of a painful disease called ergotism (known to Crivelli’s contemporaries as Saint Anthony’s Fire). To ward off the deadly illness, they carried charms carved from the root of the mandrake plant. Crivelli recalled one of the mandrake charms in the miniature head of Anthony’s wooden staff.

Saints Catherine of Alexandria and Jerome (?)

1470 On panel Philbrook Art Center, Tulsa, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress FoundationPorto San Giorgio Altarpiece

Daughter of a king and dressed accordingly, Catherine cuts a regal figure. Her crown and bejeweled clasp stand out in relief. Crivelli sculpted her accessories from gesso (pastiglia), gilded them with gold leaf, and then painted the gems to evoke rubies and pearls. Such tangible luxuries contrast with a ferociously spiked wheel. Catherine destroyed the instrument of her suffering with the power of prayer, transforming it into an emblem of her unshakable faith. Crivelli called attention to the wheel with impressive foreshortening.

© 2015 Philbrook Museum of Art, Inc., Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Saints Paul and Peter

Not in exhibition 1470 On panel The National Gallery, LondonPorto San Giorgio Altarpiece

First preacher and first pope, Paul and Peter are fundamental figures in the history of Christianity. Crivelli envisioned these spry old men as if engaged in conversation. Peter directs Paul’s attention to a passage of his open book. Below, the keys to heaven – shaped in pastiglia and covered with silver and gold – hang lightly from Peter’s wrist.

Photo: © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY.

The Virgin and Child

c. 1468–70 On panel San Diego Museum of Art, Gift of Anne R. and Amy PutnamInscribed: OPUS KAROLI CRIVELLI VENETI

Nearly naked, Christ nestles into his mother’s loving embrace. The Virgin wraps him gently in her veil and Christ tugs playfully at her pendant. By the time he painted this early work, Crivelli had already mastered the art of trompe l’oeil. Folded and sealed, a tiny note evokes petitions to the Virgin left at sacred shrines. Simulating a written prayer, Crivelli’s cartellino casts a shadow on the parapet, as if wedged between painting and frame.

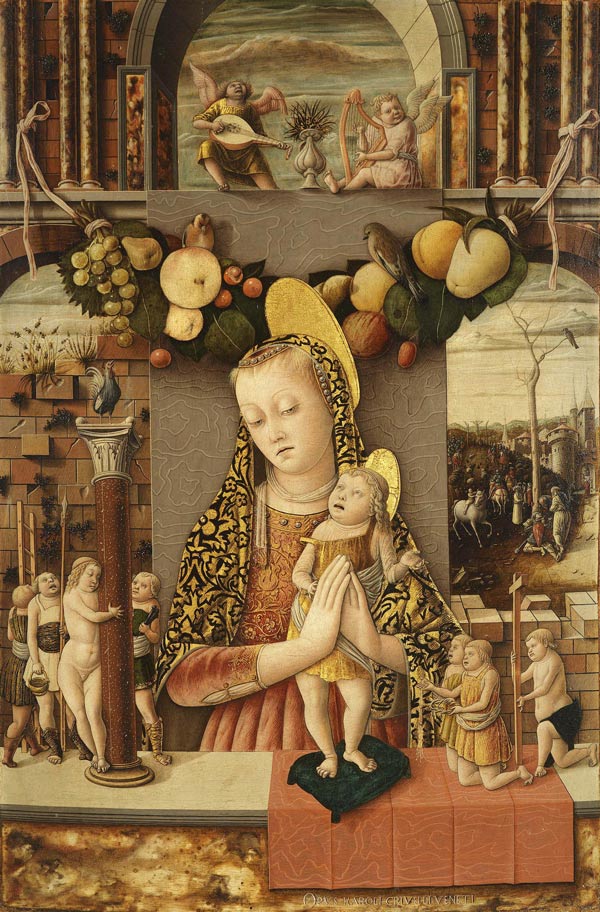

The Virgin and Child

c. 1480 On panel Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache CollectionInscribed: OPUS KAROLI CRIVELLI VENETI

Crowned with a gem-studded halo, the Virgin presides over earth in her celestial court. Purple silk moire duly honors the Queen of Heaven and a festoon celebrates the fruits of her labors. Strung from a red ribbon, this garland hangs like a celebratory offering tied to the frame, an impression reinforced by its disproportionate scale. The fly below, as oversize as the ripe cucumber, alludes to an anecdote of competition between painters in ancient Greece.

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

The Virgin and Child

1485–90 On panel National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress CollectionPoised for the viewer’s delectation, a ripe cherry balances on the parapet. The Christ Child raises one hand in benediction as his mother casts a sidelong glance at the devotee. Crivelli painted this exquisite work of intimate scale for the private devotions of a single wealthy individual. Unlike the other Crivellis in this exhibition, its frame is original, carved from the same piece of wood as the painting's support.

Photo: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with a Donor

1470 On panel National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress CollectionPorto San Giorgio Altarpiece

Inscribed: MEMENTO MEI MATER DEI REGINA CELI LETARE (Remember me, O Mother of God, O Queen of Heaven rejoice)

The enthroned Virgin Mary tenderly embraces her son. Christ clasps the apple, a symbol of the Fall and man’s redemption. The garland above them celebrates the newborn Redeemer and honors the Queen of Heaven. To frame the Virgin’s monumental figure, Crivelli painted a spectacular marble throne and inscribed it with a prayer invoking her intercession on the donor’s behalf. This unidentified cleric kneels in devotion, mouth open, as if in perpetual petition to the Virgin.

A gilded crown sparkles at the Virgin’s feet. Embossed on the flat surface in gesso relief (pastiglia), it recalls the kind of offerings of gratitude that worshippers brought to the Virgin at nearby shrines like Loreto. Situated on a ledge between Virgin and viewer, Crivelli’s crown casts a shadow. At once an actual tribute and a carefully conjured illusion, it invokes the power of material homage as the conduit to divine favor.

Photo Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

The Virgin and Child with Infants Bearing Symbols of the Passion

c. 1460 On panel Museo di Castelvecchio, VeronaInscribed: OPUS KAROLI CRIVELLI VENETI

The Virgin Mary gently enfolds her son in prayer. Christ places one hand on hers, gesturing with his other to the Holy Innocents, the children executed by Herod to protect his throne from the newborn King of the Jews. Venerated as child martyrs, they bear the instruments of Christ’s future Passion – foreshadowing his fate on Golgotha. Crivelli reveals the Crucifixion through a crumbling brick wall, a biblical metaphor for the Savior’s death.

Archivio fotografico. Photo: Matteo Vajenti, Venice.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Francis, Saint Bernardino of Siena and the Donor Fra Bernardino Ferretti

c. 1490 On panel The Walters Art Museum, BaltimoreInscribed: F B D A (probably Frater Bernardino da Ascoli, i.e. Brother Bernardino Ferretti)

Devout followers of Saint Francis in the Marches embraced their founder’s precepts with unprecedented zeal. Here a nail head protrudes through the saint’s right hand, a bodily sign of the Stigmatization that Francis received. Kneeling in prayer, the donor wears the gray habit and humble wooden clogs (zoccoli) of an observant disciple. Brother Bernardino Ferretti, one of Crivelli’s clerical clients, probably commissioned this painting for his private chapel. The monumental altarpiece depicting the Annunciation with Saint Emidius is likely another product of their close relationship.